A spiritual basis for creativity, happiness, a new way of life, reasoning, and thinking.

Learn How To Be Creative Now!

Start being intrinsically motivated and inspired!

Kamyar Alexander Katiraie Virtual Mentoring Is Available

$725 per hour using Zoom on Weekends only. I have room for only one more student at this time. My capacity is only 3 students.

Call (424) 200-2328.

Happiness requires authenticity and creativity as the fundamental components. We believe everyone is creative. What’s important is to cultivate the creative spirit from the inside out. We’ll show you how.

Practice 1

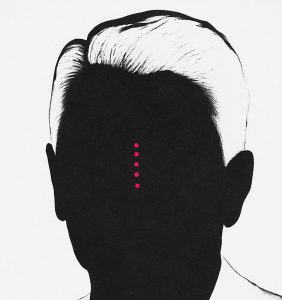

Please adhere to the guidelines for the illustration below. This is neither a trick or an attempt to deceive your mind. Looking at it scientifically, your brain uses your intuition to identify the appropriate pattern. We’ll explain why and how.

Guidelines:

1) Take a moment to unwind and focus on the four little dots in the center of the image for around 20 seconds.

2) Next, look at a nearby wall (or any other flat, one-color surface).

3) A circle of light will start to form.

4) Start blinking your eyes a few times, and a figure will start to appear.

What can you make out? Additionally, who do you see?

What creates the right image?

Once you realize the correct image by blinking, your peripheral vision, and the power of your intuition have already processed the image. You are intrinsically motivated since this feels like a riddle. Curiosity comes from within.

When you blink or close your eyes, your mind is relaxed and you are no longer focused but instead engaged. You transfer the correct image to your mind using your intuition. This is how intuition aids in the creative process. In this practice, practically every part of the creative process is engaged. It addresses everything from concentration and focus to being engaged in the activity while yet reaching creativity. The key to creativity is concentration, followed by mental relaxation and absorption so that intuition can do its job. The above practice exercises a variety of mental processes, such as attention, awareness, intuition, curiosity, the subconscious mind, and lastly the creative mind.

Practice 2

Do the exercises in the following video. This is the exact opposite of the first practice you just did. In the video below you must focus on the + sign between the two images. The Guidelines are at the start of the video.

Another one:

These practices involve peripheral vision. In our first practice all of the patterns of the picture were present but jumbled. We didn’t add any irrelevant pattern to the picture. We allow your peripheral vision to correctly concentrate on the image and put it together properly. Even though it was jumbled, we provided accurate information (but jumbled) to your peripheral vision. In essence, we altered the reality of the patterns rather than changing them. This is significant, which is why I’m highlighting it. Have you ever played with jumbled words? This is kind of the same. Next time you play with jumble words, close your eyes and check to see if you can solve it better.

In the second video, we fed (or coerced) extraneous or irrelevant information into your peripheral vision by the speed of the video. Your peripheral vision didn’t have any issues in our first practice. However, in the second, your peripheral vision was unable to appropriately interpret the patterns. In other words, your intuition will not be able to properly assist you once you have given your brain information that is unclear or irrelevant.

So in real life what do you need to do? Get rid of the information that is holding you back. Most successful people are able to focus on the important facts and avoid letting extraneous information cloud their judgment or cause them to make poor decisions.

The practices above are commonly known as optical illusions. That’s accurate. But, looking at it scientifically, there isn’t any deceit or trickery going on. Even though they are optical illusions, they have a sound scientific foundation that specifically includes the brain and peripheral vision.

Our Main Theory

Searching for nobility and virtuosity (finding virtue and nobility with inner truth and passion) + Concentration and focus <——> Imagination (Visualization) + Insights + Learning + Intuition <———--> Goal Setting, Hard Work, Determination, Teamwork, and Creativity Strong feelings of accomplishment and originality

The formula above is the most important aspect of this book. We believe that is how creativity takes place. It is a mind map. In practice 1, this formula worked.

Regarding practice 1, I have to emphasize that many people have tried to create the same effect on other people, but it has never worked.

Look at image below. Do the same thing on image below. Concentrate for 20 second on 4 dots in middle of image.

This is supposed to be Obama: source: youtube.com/watch?v=03Hx280B_mk

Notice how it doesn’t fully work—or only works halfway. Does it have something to do with being Noble and Virtuous?

How abut the most minimum image below?

Increase your focus time to more than 30 seconds. Who? Do your best. Hint:

95 out of 100 hardcore republicans were able to identify the image while only 5 democrats were successful.

I firmly believe—and this is a central theory explored in the book—that true creativity flourishes when the creator regards their chosen subject as noble and virtuous. In other words, for creativity to reach its fullest expression, the individual must feel a deep sense of respect, purpose, and moral value in what they are creating. However, what one person considers noble and virtuous can vary greatly from another’s perspective, reflecting the unique values, experiences, and passions that shape each individual.

For instance, take an Argentine Tango dancer who channels their creativity through the art of dance. To them, the intricate movements, the emotional connection, and the cultural heritage embedded in Argentine Tango represent something profoundly noble and virtuous. Their creative energy is fueled by this reverence, making their artistic expression authentic and meaningful. On the other hand, someone else might find their sense of nobility and virtue in the visual arts—drawing and painting, for example. For this person, the act of bringing images to life on a canvas is where their creative spirit thrives.

This diversity in what we hold sacred underscores the deeply personal nature of creativity. It highlights that there is no universal standard for what should inspire us; rather, creativity is empowered when we discover and embrace a subject that resonates with our own sense of meaning and integrity.

Jonny Thomson – @philosophyminis

How To Achieve Happiness?

Jonny Thomson – @philosophyminis

We say ignore the irrelevant and he says ignore what you cannot control. Do you see the similarities?

This webiste or book is basically created to guide you on how to become the Camel, Lion (without negativity) and Child (or child-like) all at the same time.

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift, and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.” ~ Albert Einstein

Jonny Thomson – @philosophyminis

Another Important Theory

A very important theory of this book is about observation. Notice in practice above we are observing unfamiliar image in a familiar way. Creativity is actually observing familiar things in an unfamiliar ways. I like to give Cubism as an example.

Pablo Picasso’s 1909 painting Femme Assise set a record price for any Cubist work at auction—$63.6 million. It is also the highest price to be paid for a painting in London in over five years. The work has been in a private collection since 1973, when it was purchased for approximately $833,000.

Here are several more examples:

Literature

-

Example: James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922)

-

Joyce uses stream-of-consciousness, fragmented narrative, and interior monologues, making the familiar act of storytelling an unfamiliar, challenging experience that mirrors the complexity of thought.

-

-

Example: Jorge Luis Borges’ Short Stories

-

Borges blends philosophy, reality, and fiction, twisting ordinary concepts like libraries, mirrors, and labyrinths into profound explorations of perception and reality.

-

3. Architecture

-

Example: Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (1997)

-

Gehry took the conventional idea of a museum building and reimagined it as a flowing, sculptural form. The familiar function of the building is transformed by an unfamiliar, dynamic form that alters how people experience space.

-

-

Example: The Pompidou Center, Paris (Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers)

-

Here, the building’s structural elements and utilities are exposed on the exterior, reversing traditional architecture to challenge norms about what a building should look like.

-

4. Product Design

-

Example: The Dyson Vacuum Cleaner

-

Dyson redesigned the vacuum by eliminating bags and using cyclonic separation, making people see the everyday vacuum cleaner in a new way with enhanced performance and design.

-

-

Example: The Swiss Army Knife

-

A familiar tool (knife) is transformed into a multifunctional gadget, encouraging users to rethink utility and compactness.

-

5. Film and Theater

-

Example: Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000)

-

The film’s story unfolds in a non-linear way, reversing chronological order. This makes audiences experience the familiar concept of a mystery story in a new, disorienting way.

-

-

Example: Bertolt Brecht’s Epic Theater

-

Brecht broke the “fourth wall,” directly addressing audiences and disrupting traditional theater immersion to make them critically observe the play and social issues.

-

6. Science and Technology

-

Example: Einstein’s Theory of Relativity

-

Einstein challenged the familiar Newtonian view of time and space, showing that both are relative rather than absolute—completely changing how we observe the universe.

-

-

Example: The Invention of the Telephone (Alexander Graham Bell)

-

Bell transformed the familiar concept of voice communication by enabling long-distance speaking, reshaping how people relate and communicate.

-

7. Everyday Life & Cognitive Psychology

-

Example: Mindfulness Meditation

-

By observing everyday sensations and thoughts non-judgmentally, practitioners see their familiar internal experience in a completely new way, often leading to creative insight and emotional healing.

-

-

Example: Lateral Thinking (Edward de Bono)

-

Lateral thinking encourages problem-solving by approaching problems from indirect and unexpected angles, breaking the conventional logical flow.

-

These examples show how creativity is deeply connected to perspective shifts—whether in sound, story, space, tools, narrative structure, science, or cognition. The key is observing or using the familiar in ways that break expectations and invite new understanding.

How Paradigm Shifts Relate to Creative Observation

-

Paradigm = A Mental Model or Framework

-

It’s the set of assumptions, beliefs, and methods through which people interpret the world.

-

Normally, we observe and interpret phenomena within the boundaries of this framework—so what we see feels “familiar” and natural.

-

-

Paradigm Shift = Changing the Framework Itself

-

When a paradigm shifts, people start observing and understanding the same reality through an entirely different lens—an unfamiliar way.

-

This is the essence of our theory: seeing something familiar but in an unfamiliar way leads to creative breakthroughs.

-

Examples of Paradigm Shifts as Creative Observation

-

Scientific Revolution: Copernican Heliocentrism

-

Before Copernicus, the accepted paradigm was that Earth was the center of the universe (geocentric).

-

Copernicus observed the familiar night sky but through a new lens—heliocentrism—placing the sun at the center.

-

This radically changed humanity’s view of the cosmos, a massive creative re-interpretation.

-

-

Quantum Mechanics vs. Classical Physics

-

Classical physics viewed particles and waves as separate, predictable phenomena.

-

Quantum mechanics introduced a new paradigm: particles have wave-like properties and exist in probabilistic states.

-

Scientists saw the same natural world but in a fundamentally different way.

-

-

Art: From Realism to Impressionism and Beyond

-

The shift from precise, detailed realistic painting to Impressionism was a paradigm change in art.

-

Instead of replicating the visual scene exactly, artists focused on light, color, and fleeting impressions—changing the way viewers observed familiar subjects.

-

Why Paradigm Shifts Are the Ultimate Creative Acts

-

They transform the “rules of the game.”

Instead of innovating within existing rules or perspectives, paradigm shifts rewrite the rules, changing what is possible or visible. -

They require deep observation and questioning of assumptions.

To change the paradigm, one must first observe where the current model fails or limits understanding—thus requiring truly fresh perspectives on familiar realities. -

They often start with an act of creative re-interpretation.

Whether it’s a scientist, artist, or thinker, the shift begins by re-seeing familiar data, experiences, or objects differently.

I like to present paradigm shifts as creative leaps that represent the purest form of “observing familiar things in unfamiliar ways.” They demonstrate how creativity isn’t just about small changes or new combinations, but can sometimes mean completely transforming the way reality is seen and understood.

Intuition: The Mother of All Paradigm Shifts

Paradigm shifts are profound transformations in the way we perceive and understand reality. But what sparks these radical leaps? At the heart of every paradigm shift lies intuition—the deep, often unconscious insight that allows us to glimpse a new framework before it can be fully articulated or logically proven.

Why Intuition Is the Source of Paradigm Shifts

-

Intuition Sees Beyond Existing Frameworks

-

Intuition operates beneath the surface of conscious reasoning. It is capable of synthesizing vast, complex information rapidly, without relying on the step-by-step logic that current paradigms demand.

-

This “gut feeling” or inner knowing allows individuals to perceive connections and possibilities that don’t yet fit within accepted rules or evidence.

-

-

Intuition Sparks the Creative Leap

-

Paradigm shifts cannot be arrived at by incremental reasoning alone because they require thinking outside the box—redefining the box itself.

-

Intuition is the mental faculty that breaks through the constraints of conventional thought, offering new insights that seem to come “out of nowhere,” yet feel undeniably true.

-

-

Intuition Precedes Rational Proof

-

Often, intuitive insights precede and guide formal scientific, artistic, or philosophical development.

-

For example, Einstein described how his theory of relativity began with a “thought experiment” — a deep intuitive insight about the nature of light and time — well before it was mathematically formalized.

-

-

Intuition Connects Disparate Information

-

Intuition excels at pattern recognition and linking seemingly unrelated facts, enabling the birth of new paradigms that unify knowledge in novel ways.

-

This ability to synthesize across domains is essential for paradigm shifts, which often require broad, integrative thinking.

-

Examples Where Intuition Led Paradigm Shifts

-

Albert Einstein and Relativity

-

His insight that time and space are relative arose intuitively from contemplating the behavior of light, long before the complex mathematics was worked out.

-

-

Niels Bohr and Quantum Mechanics

-

Bohr’s intuition about the atomic structure led to the revolutionary quantum model, challenging classical physics.

-

-

Steve Jobs and Personal Computing

-

Jobs intuitively grasped that computing should be personal, accessible, and design-centric—transforming an entire industry with a new paradigm of human-computer interaction.

-

-

Marie Curie and Radioactivity

-

Curie’s intuition that certain materials emitted unknown energy opened up a new field, fundamentally changing physics and chemistry.

-

Intuition in Creative Fields Beyond Science

-

Artists like Picasso often describe creative breakthroughs as intuitive moments—sudden visions or feelings about how to represent a subject differently, breaking free from classical rules.

-

Writers like James Joyce trusted intuition to experiment with language and narrative structures that defied traditional storytelling.

-

Entrepreneurs and Innovators rely on intuition to identify unmet needs and envision products or services no one else has considered.

Intuition and This Book’s Core Thesis

This book’s focus on creativity as “observing familiar things in unfamiliar ways” naturally leads to intuition as the origin of such observations. It is intuition that:

-

Pushes beyond habitual perception

-

Enables new mental models and perspectives

-

Fuels the leap from known to unknown

-

Ultimately drives paradigm shifts that redefine reality itself

In this sense, intuition is the mother of all paradigm shifts, the primal creative force that empowers us to reimagine the world at its deepest levels.

Predicting the next paradigm shift is always challenging because, by nature, paradigm shifts come from seeing the world in fundamentally new ways—often unexpected and emerging from deep intuition or revolutionary discoveries.

But based on current trends across science, technology, and society, here are some promising candidates for the next paradigm shift:

1. Consciousness and Mind-Body Integration

-

Increasing research in neuroscience, quantum biology, and philosophy is challenging the traditional mechanistic view of the brain as just a biological computer.

-

The next paradigm might integrate consciousness as a fundamental aspect of reality, not just a byproduct of brain activity. This could revolutionize medicine, psychology, AI, and our understanding of self.

-

It would mean seeing familiar human experience through an entirely new lens—melding science and spirituality.

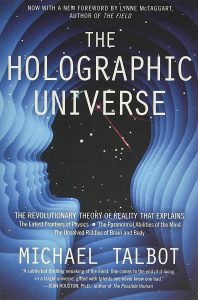

Consciousness: Beyond the Material

The traditional view sees consciousness merely as a byproduct of brain activity. Emerging research in quantum mechanics, neuroscience, and philosophy suggests consciousness itself may be fundamental to reality. Imagine a future where our deepest intuitions confirm a universe woven from consciousness and information rather than solely matter. This paradigm shift could redefine everything from medical treatments to artificial intelligence, reshaping our understanding of identity and existence itself.

2. Post-Materialist Science

-

Current science largely assumes a materialist worldview: matter and energy are primary.

-

Emerging theories (in quantum physics, information theory, and cosmology) suggest information or consciousness might be more fundamental than matter.

-

This shift would change how we see the universe—from a “machine” to a vast network of information and awareness.

3. Human and AI Symbiosis

-

Rather than AI replacing humans, the next paradigm may be a deep integration of human intelligence with artificial intelligence, enhancing cognition, creativity, and decision-making.

-

This will reshape identity, work, ethics, and society’s structure.

4. Ecological and Systems Thinking

-

The traditional human-centered worldview is shifting toward holistic, systems-based thinking about Earth’s ecosystems.

-

Future paradigms may deeply integrate humans as part of ecological networks, prioritizing sustainability and interdependence rather than exploitation.

5. Radical Decentralization and New Social Models

-

Technologies like blockchain and distributed ledgers challenge centralized authorities and institutions.

-

New social paradigms might arise around decentralized governance, trust, and community organization—reshaping politics, economics, and cultural norms.

Why These Could Be the Next Paradigm Shifts

-

They challenge fundamental assumptions about who we are, what reality is, and how we relate to technology and nature.

-

They demand new ways of observing and understanding the world—fitting perfectly with your core creativity theme.

-

Each requires a leap of intuition, not just incremental knowledge, to reimagine familiar realities.

Human-AI Integration: Collaborative Creativity

Today, AI often sparks fear of displacement or redundancy. But what if the future reveals AI as an extension, not replacement, of human intuition and creativity? Rather than viewing AI as merely tools or threats, we might enter an era of symbiotic partnership, amplifying human creativity, insight, and decision-making. This integrated paradigm could revolutionize education, art, science, and innovation, guiding humanity into a radically creative coexistence with technology.

Ecological Interconnectedness: Holistic Awareness

We have traditionally viewed humans as separate from nature, managing ecosystems as external entities. The next paradigm shift may lead us to see humanity fundamentally embedded within ecosystems, recognizing our deep interdependence with the environment. This shift demands intuitive awareness—seeing and feeling nature’s rhythms and interconnected systems. This new perspective could reshape societies, economies, and cultures around sustainability and collective flourishing.

Decentralized Societies: The Power of Networks

Our modern world depends heavily on centralization—centralized authorities, economies, and infrastructures. However, decentralizing technologies like blockchain could profoundly change this. Imagine future societies where trust, governance, and resources are distributed, transparent, and network-based. This decentralization fosters creativity, autonomy, and collaboration, unleashing unprecedented social innovation and community empowerment.

Cultivating Intuition for Future Paradigms

At the heart of these potential shifts lies intuition—the driving force enabling us to transcend current perceptions and reimagine the familiar anew. Cultivating intuition becomes essential for individuals and communities seeking not just to anticipate but actively shape these paradigms. Creativity in the future will depend on our capacity to intuitively embrace unfamiliar perspectives, connections, and possibilities.

These future paradigm shifts are not guaranteed—they await the intuitive insights, courage, and creativity of those bold enough to see the familiar world in radically new ways.

Lack Of Intuition?

“You’d better learn secretarial skills or else get married.” Modeling Agency, rejecting Marilyn Monroe in 1944

“You ought to go back to driving a truck.” Concert Manager, firing Elvis Presley

“Can’t act, can’t sing, slightly bald, can dance a little.” A film company’s verdict on Fred Astaire’s screen test

“We don’t like their sound,” Decca Records said in turning down a recording contract with the Beatles.

“The telephone has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us.” Western Union Memo

“The telephone may be appropriate for our American cousins, but not here, because we have an adequate supply of messenger boys.” A British expert group evaluating the invention of the telephone

“The horse is here to stay, but the automobile is only a novelty.” A Michigan Banker advises investing in the Ford Company.

Intuition Gathering Strategies

Once you finish this online book, you will realize why those quotes are relevant. Just to give you a hint, intuition is the key.

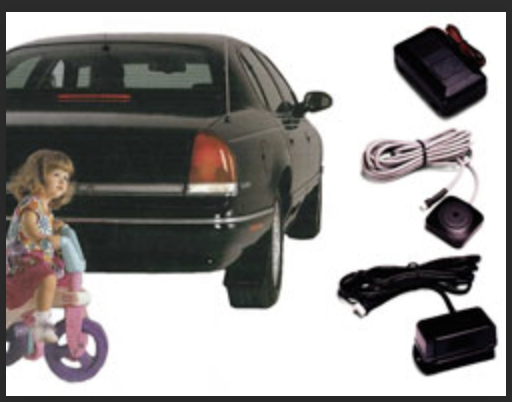

By pure luck, the manufacturer of the Club anti-theft device (for the steering wheel) approached me in 1992. Club was interested in marketing my patented invention, the famous Ultrasonic Blind Spot Back-Up Alert that is installed in almost every car today. Of course, they had to wait 17 years for the patent to expire. The club sold it for $79.99. I received $7.99 in royalties. We sold approximately a million backup alarms worldwide between 1993 and 2000.

I, Marilyn Monroe, Fred Astaire, the Beatles and Mr. Ford were lucky!! I want you to think about this a bit deeper. I wonder how many talented people were passed by companies, bosses or managers who did not have enough intuition to appreciate talent or they were worried to lose their job or replaced by this new talented guy. Think about it!!

What is intuition? When making a decision, the brain uses intuition to draw from previous experiences, and patterns. When you have an intuitive moment, it happens so quickly that your response is unconscious. We only have a general sense of what is right or bad or how something ought to be.

The creative process in first practice serves as an illustration of a mind map in which you concentrated, envisioned, discovered virtue, attained creativity, and finally had an Aha! or inspirational moment.

Happiness and authenticity share a profound philosophical bond, as both stem from a deeper alignment between the self and the world. To live authentically is to live in accordance with one’s true nature—free from societal masks and external pressures. Perhaps that is why non-conforming people are more happy. This journey toward authenticity is inherently guided by intrinsic motivation, the inner drive that arises not from external rewards but from the inherent satisfaction of actions that reflect our true selves. In essence, authenticity is a form of existential freedom, where one’s choices and actions are rooted in personal meaning and individual truth rather than external validation.

Philosophers like Søren Kierkegaard and Jean-Paul Sartre argue that living authentically requires embracing the freedom of self-creation, even in the face of societal expectations. This self-determined existence is where intrinsic motivation plays its vital role—it propels individuals to pursue actions that resonate with their essence, rather than conforming to external motivations like success or approval. As one grows more authentic, they create a life that is harmonious with their innermost desires and values, thus fostering a sense of eudaimonic happiness—a happiness rooted in self-realization and personal growth.

In contrast, when people stray from their authentic selves, acting solely based on extrinsic motivations such as social approval, they often feel disconnected or incomplete. This detachment from their true nature leads to inner conflict and an erosion of well-being. Ultimately, happiness becomes not merely an emotional state but a byproduct of living authentically—pursuing a life aligned with one’s intrinsic motivations, where the joy of being oneself naturally arises.

The relationship between happiness and authenticity is not just a superficial one but a deep philosophical inquiry into the nature of the self and how we engage with the world around us. As we mentioned, authenticity, as philosophers like Sartre and Kierkegaard suggest, is the path to self-fulfillment, as it entails living in congruence with one’s core beliefs, values, and desires. When individuals act authentically, they make choices that reflect their true nature rather than conforming to societal expectations or external pressures. This creates a sense of existential freedom, where individuals accept responsibility for their choices, even in the face of societal constraints or fear of judgment. In this sense, authenticity is not merely about self-expression but about ownership over one’s existence, which is essential for achieving lasting happiness.

At the core of this philosophy is intrinsic motivation, the inner drive that compels people to pursue goals that are inherently satisfying and meaningful to them. Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory posits that people are most fulfilled when they act from a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness—all of which are heightened when they follow intrinsic motivations. These self-driven actions align with authenticity, as they reflect the inner values and passions that define who a person truly is. Pursuing goals that stem from intrinsic motivation leads to what Aristotle might describe as eudaimonia, a form of happiness rooted not in fleeting pleasures but in the fulfillment of one’s true potential and purpose.

The importance of intrinsic motivation is also crucial to understanding how extrinsic motivations can derail happiness. When people prioritize external validation—whether it be through wealth, status, or the approval of others—they distance themselves from their authentic desires. This creates a tension between their internal world and the external roles they feel they must fulfill. According to Existentialist philosophy, this disconnect can lead to a state of alienation, where individuals no longer recognize themselves in the roles they play, and this can breed a sense of meaninglessness or existential anxiety. Authenticity, by contrast, provides an antidote to this alienation, as it encourages individuals to live in accordance with their true nature, even if that path is uncertain or unconventional.

Moreover, authenticity allows for authentic relationships—another vital component of happiness. When individuals act authentically, they form deeper connections with others, as they are not hiding behind societal masks or engaging in surface-level interactions. These genuine relationships foster trust, intimacy, and a sense of belonging, which are essential ingredients for emotional well-being. Brené Brown, a leading researcher on vulnerability and authenticity, highlights how being authentic in relationships requires vulnerability, but it is through this vulnerability that real connections are made. Thus, living authentically not only nurtures personal happiness but also enhances relational satisfaction, further deepening the overall sense of well-being.

In contrast, the pursuit of extrinsic goals such as wealth, status, or power, often results in what Erich Fromm describes as a “having” mode of existence, where one’s identity is wrapped up in possessions or external achievements. This mode of living can lead to chronic dissatisfaction because it is not grounded in the essence of who we are but in the fleeting approval of others or material success. On the other hand, an “authentic being” mode focuses on personal growth, self-expression, and internal satisfaction, all of which contribute to long-lasting happiness. The Stoic philosophers also emphasized this idea, arguing that external circumstances are beyond our control, and true contentment can only come from aligning with one’s values and accepting life as it is.

Ultimately, happiness is not a static state but a dynamic process of becoming—one that is intimately tied to living authentically. When individuals embrace who they are, act from a place of intrinsic motivation, and engage meaningfully with the world around them, they cultivate a life of purpose and joy. Authenticity is, therefore, not just a moral imperative but a path to deep, sustained happiness that transcends the superficial rewards of conformity and external validation. By embracing authenticity, individuals can navigate life’s uncertainties with a sense of inner peace, knowing that their happiness is grounded in the truth of who they are. Almost at the bottom of this page, you will encounter stories of individuals with eccentric traits. Their lives serve as a testament to the beauty of authenticity, revealing that true happiness often emerges when we embrace our unique essence, rather than conform to the expectations of others.

Creativity and Mind Map

Here is our mind map:

Intrinsic Motivation + Concentration/Focusing or a strong form of infatuation, intrigue, or absorption —--> Imagination (Visualization) + Intuition —--> finding Virtue ——-> Strong feelings of inspiration, accomplishments, or the Aha! moment.

Our approach to creativity is more about enjoyment, inspiration, and inner motivation. It involves setting up the right circumstances so that you can readily inspire your thoughts and feel intrinsic motivation. Everything is achievable once you are inspired, including problem-solving, creativity, self-improvement, intuition, and high levels of performance.

Don’t you wish you could have a “aha” moment where the solution suddenly appears to you in an original and inspirational way in every challenging circumstance? Our goal is for you to experience the same ease of inspiration, joy, and creativity as you did above.

If you correctly train your mind and strive to be intrinsically driven, you can be creative in practically any setting. The next Steve Jobs or Picasso could not be you. We didn’t make that promise. However, we guarantee that having little, inspired, and creative experiences will make you happy and successful. We guarantee that you’ll develop a fresh sense of independence and autonomy and find it simple to make new acquaintances. You’ll gain the respect of your coworkers and potentially move on to your next opportunity. We think how much you find what you do noble and virtuous determines how happy and successful you are. In other words, the strength of your intrinsic motivation, the degree to which you see the virtue in what you do, and the reasons behind your actions translate to creativity and success. Finding virtue and passion in what you do is the key.

Finding virtue is what? Finding virtue does not necessarily equate to “liking”. For the creative process, liking is not profound enough. Steve Jobs wasn’t content to limit his inventions to computers. Steve Jobs believed it was noble and virtuous to make home computers accessible to everyone. Fighting for freedom and equal rights was not just something Mandela and Martin Luther King “liked”. They thought that having freedom and equality was noble and virtuous. John F. Kennedy thought holding public office was a noble pursuit and that civic participation was essential to a flourishing democracy. A generation was motivated to help fix the world both at home and abroad by Kennedy-era initiatives like the Peace Corps.

The international drive to eradicate the Guinea worm disease has been spearheaded by President Carter.

By using his position to promote international peace and the fight against disease, President Carter has reimagined what it means to be an ex-president. His greatest achievement to date is the nearly complete eradication of Guinea Worm Disease. The Guinea worm has a significant economic impact. The disease occurs during the planting and harvesting seasons, when there is a strong demand for labor and workers must drink a lot of water, which increases the risk of reinfection. According to one research, rice farmers in southeast Nigeria lost the equivalent of $20 million annually because they were unable to work. According to the same report, more than 60% of students miss school due to guinea worm disease or having to work for relatives who have the disease.

Since 1986, The Carter Center has taken the helm of the global effort to eradicate Guinea worm disease, collaborating closely with national health agencies and regional populations. Following the eradication of smallpox, guinea worm disease is expected to follow suit. According to a human rights organization, there were just 22 occurrences of the deadly Guinea worm sickness in 2015.

Introduction to our method

Our method consists of:

1) Mindfulness to overcome difficulties and negativity in the mind and to be able to find virtue

2) Discovering fresh intrinsic motives via independence and observational abilities

3) Finding virtue leads to discovering creativity

4) Involving creating innovations

We go over the value of a mind map and how to create one in the first chapter. We look at a method-based practice in the second chapter.

The Aha experience might not be feasible without creativity (or originality). The Aha moment might be triggered by the sensation of having produced something original and novel.

Broad definition of the mind map:

Finding Virtue (finding virtue with inner truth and passion) + Concentration + Focusing or a strong form of infatuation or intrigue (Intrinsic Motivations) Imagination (Visualization) + Insights + Learning + Intuition ———--> Goal Setting, Hard Work, Determination, Teamwork, and Creativity ——-> Strong feelings of accomplishment, inspiration, and originality

The power of Intrinsic Motivations and Intuition in the creative process

In the foregoing exercise, we had no trouble using our intuition. This approach aims to make it easier and more natural to identify intuitive patterns. We will show you how to supplement incomplete information with intuition. You will turn to your intuition once you realize you can’t gather all the data. Your emotions and gut instinct will be added to the creative process. Intuition entails letting up of rational thought and having faith in the unconscious’ perception. You’ll notice that new information, like fresh melodies, readily enters awareness when you’re in an intuitive or mindful state. This novel information might not always make sense and may contain many surprises. The Mind Map’s activities are all connected through intuition.

When we are not actively thinking about anything, we are more receptive to unconscious mind. Daydreams are quite helpful in the search for motivation because of this. Have you ever heard that for some people, the solution may ultimately come to them in the early hours of the morning or even when they are taking a shower? Now is the moment to let your intuition come up with the solution.

More on Intuition

Intuition is a skill that can be learned and developed through life experiences. Consider this example: In an experiment, both chess grandmasters and beginners were shown a chess configuration from an actual game and asked to duplicate it. The chess professionals duplicated the pattern with 95% accuracy, while beginners only achieved about 25% accuracy. Chess configuration based on actual game is very much like the first practice you did where the patterns were actual but jumbled.

The same process was repeated, but this time the chess pieces were arranged randomly and not from an actual game. Both experts and novices scored approximately 25% in this second trial. Chess configuration based on random placement and not actual game is very much like the second practice you did where speed of the video injected misinformation.

Why did the masters perform similarly to the beginners in this scenario?

Chess grandmasters retain not just a collection of patterns but also an understanding of their significance. When the chess pieces are placed randomly, the configuration has no meaningful context for them, rendering their intuition ineffective. The masters scored 25% because the random arrangement provided irrelevant information, again akin to what we discussed earlier in our second practice.

This example illustrates that intuition relies on meaningful patterns and context. When presented with random or irrelevant information, even the most experienced individuals cannot leverage their intuitive skills effectively.

The vast array of patterns stored in long-term memory significantly contributes to an expert’s intuitive ability. For instance, chess grandmasters have around 50,000 real patterns from actual games saved in their long-term memory.

Experts can quickly connect salient environmental signals to frequently recurring patterns, allowing them to solve problems and make decisions efficiently. This ability to use experience to spot important patterns and predict the dynamics of a situation is a hallmark of intuitive decision-making.

Experienced decision-makers forecast how the present will evolve into the future by actively visualizing people and objects and imagining how they will transform through various transitions. The goal of this guide is to establish mental frameworks that make it easier to recognize new patterns and foster creativity in any situation. It is also noteworthy that experience alone might not always be the answer. Observing a 15-year-old defeat a 60-year-old grandmaster in chess makes it clear that some abilities are simply gifted by nature.

How much do we rely on our intuition? Unfortunately, the answer is not much. This gap starts in the classroom, where intuition is not taught. Instead, we are trained to seek accurate information and the correct answers. However, in real life, even with all the necessary data, there can still be uncertainties. This is where instincts come into play. When faced with a gap, most individuals give up, but you shouldn’t. With our strategy, you will come to appreciate these gaps.

“It is through logic that we prove It is by intuition that we discover.” Henri Poincare

Bach spoke about how musical inspiration flows naturally. When asked where he got his melodies from, he said, “The problem is not finding them; it’s—when getting up in the morning and getting out of bed—not stepping on them.”

People that are creative either inherently are or learn to be:

1) Self-learners who are naturally inclined to learn new things, mindful, find the activity to be noble and righteous, and have amazing concentration and visualization abilities.

2) Possess uncommon, unconventional abilities for observation and focus.

3) The desire for challenges; the constant quest for virtue and nobility in the work (it must be a noble task). If not, it is not right or noble, and it is not something that should be done.

4) Refuse to accept “no” as an answer.

5) Takers of Risks; Intuitive.

6) Are intelligently eccentric.

7) Face challenges head-on rather than avoiding them.

8) Sincere; liberated; inquisitive.

9) Accepting their vulnerability and not being afraid to show their vulnerability or to feel shame.

10) Childlike; quickly bonds with like-minded individuals.

11) Capable of mental reprogramming.

12) Complete control over what should be brought to their attention (again, observation), as well as how to interpret it properly for creativity.

13) Imagination and vision make it simple to foster creativity.

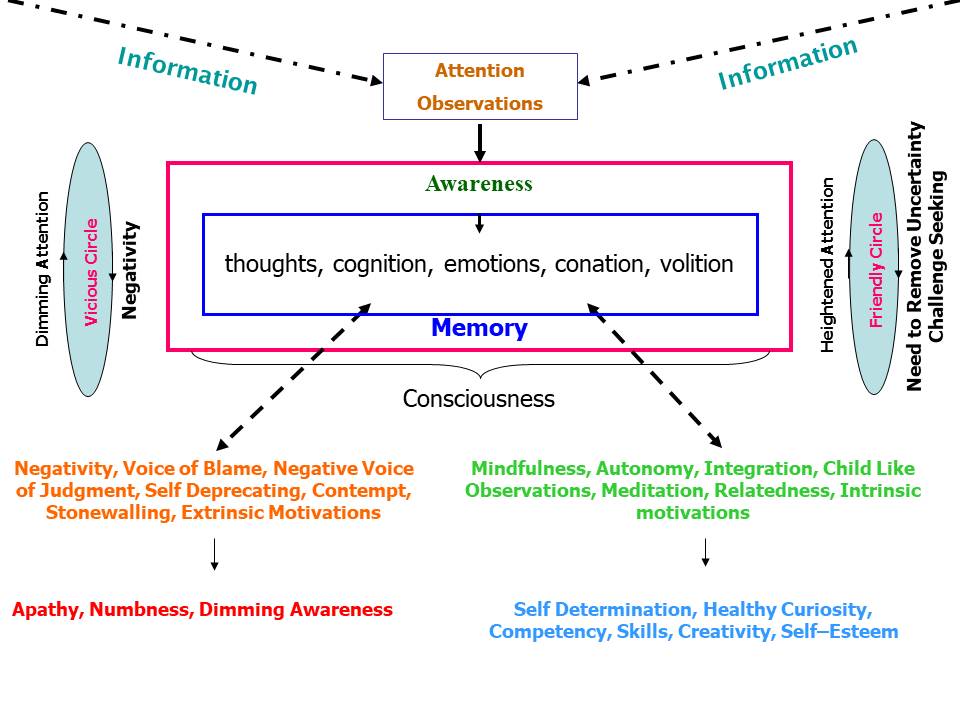

Perhaps the human consciousness functions something like a productive information processing system. You need to grow better at observing and listening (all the inputs) if you want to use your awareness to its fullest potential. As well as rewire the brain’s neural network to produce the proper creative process. We’ll demonstrate for you.

|

|

We want to train your mind to learn to move from the left side to the right side of the illustration above to feel inspired, to get absorbed easily in new tasks, to learn to create new pattern of intuition easily, to innovate and to create.

|

Jonny Thomson – @philosophyminis

Think of a chocolate factory. Input must be chocolate ingredients for this factory to generate chocolate. Correct? Additionally, the equipment has to be set up to make chocolate. Correct? You now need to accomplish two things in order to alter this factory’s output. Change the factory’s input before changing the equipment. In other words, both input and machinery must change to get a different output.

In his book Seven Habits, Stephen Covey provides an intriguing example. A guy on a bus notices a group of loud and disruptive children. He becomes angry and furious. Let’s specify the input first. The input is the obnoxious noise made by a group of rambunctious children. Anger is the result of an imbalanced mental region that also perceives children as being unruly and in need of restraint. Do you see the input and the machinery in this example?

The man learns from the their father that the mother of the children just passed away. The input is now updated, as you can see. It is now characterized as subliminal disobedience rather than merely annoying noise. It’s amazing how quickly the mind transitions from agitation to tolerating. In fact, the mechanism develops into an instinctively sensitive portion of the brain. He is now employing his empathetic or sympathetic part of his brain. You might argue that the unstable and imbalanced portion of his brain gets taken over by the empathetic portion. But note how both brain regions are driven by intuition.

When you encounter a similar circumstance in the future, ask yourself, “What is the input I am receiving?” Then, ask yourself, What region of my brain is handling this input? If I do a different analysis of the information, can I intuitively process it in a different manner?

Jonny Thomson – @philosophyminis

Our approach focuses on teaching you superior information processing and observational abilities.

You feel energized and are capable of accomplishing incredible goals if you can shift from the left side of the picture above to the right side in any circumstance. You are now prepared to develop new patterns of intuition, to always trust your gut, and to experiment with your creative side. We’ll demonstrate how this change is doable. I want to underline that in the figure above, our left and right sides are not the same as the left or right hemispheres of the brain. Our example from before just serves to highlight how our awareness typically operates in two modes. Sometimes we process information from the left side based on circumstances from previous lives and our prior observations. We’ll demonstrate that we can put a permanent end to this.

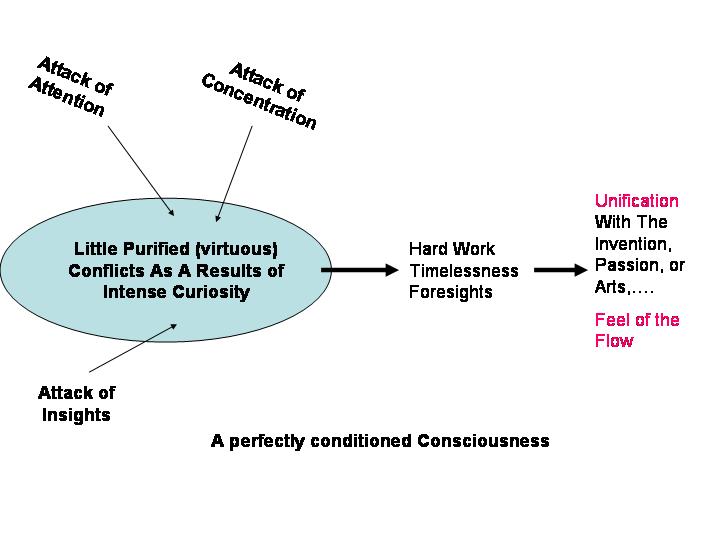

A virtuous task is one that is produced by an inspired and fully conditioned awareness, whether it be for the sake of improving life (inventions), purely aesthetic enjoyment (arts), or the love of the activity itself (dancing, photography, woodcarving, rock climbing, etc.). We launch a merciless assault on these obstacles as soon as they are established in order to reach the Aha moment. These noble difficulties often produce hard effort, timelessness, and foresight as their outputs or outcomes.

|

|

Once on the right side, a curious mind needs virtuous challenges. You are challenging newly created pattern of intuition to excel itself or to complete itself. It more like: let’s see if I am right.

|

|

Child Like (not childish) Thinking Pays

|

|

Be Authentic, Vulnerable, Let Mindfulness Solve

|

|

Simon Sinek: How great leaders inspire action

|

|

Secret To Creativity: Be Authentic

|

Baruch Spinoza

(You can take a man out of religion, but you cannot take religion out of a man.” Alex Katiraie)

Early Life and Background

Baruch Spinoza, born on November 24, 1632, in Amsterdam, was a philosopher of Sephardic Jewish descent. His family had fled persecution in Portugal and found refuge in the relatively tolerant environment of the Dutch Republic. Spinoza was raised in a community that valued religious scholarship, and he received a traditional Jewish education. However, his inquisitive mind soon led him beyond the confines of religious orthodoxy.

Intellectual Development and Key Philosophical Contributions

Spinoza’s philosophical journey was deeply influenced by the works of René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes. His early exposure to Cartesian philosophy shaped his thinking, but Spinoza eventually developed his own, more radical ideas. He rejected the dualism of Descartes and instead proposed a monist philosophy in which God and nature are one and the same. This idea was central to his magnum opus, Ethics, published posthumously in 1677.

In Ethics, Spinoza laid out a rigorous, geometric method to explain his ideas. He argued that everything that exists is a part of God, or substance, which is the underlying reality of the universe. This led to his pantheistic view of the world, where God is not a transcendent being but is immanent in the world. Spinoza’s philosophy was groundbreaking as it challenged the prevailing religious and philosophical doctrines of his time.

Ethical and Political Philosophy

Spinoza’s ethical views were closely linked to his metaphysics. He believed that true happiness comes from understanding the nature of reality and aligning oneself with it. According to Spinoza, emotions are the result of inadequate knowledge and are the source of human suffering. By cultivating reason, individuals can achieve a state of “blessedness” or intellectual love of God (amor Dei intellectualis), which is the highest form of happiness.

Spinoza also made significant contributions to political philosophy, particularly in his Theological-Political Treatise (1670). In this work, he argued for the separation of philosophy and theology, advocating for freedom of thought and speech. Spinoza was a strong proponent of democracy, believing that the best form of government is one that allows individuals the freedom to think and express themselves.

Life Achievements and Legacy

Spinoza’s life was marked by intellectual independence and courage. Despite being excommunicated from the Jewish community in Amsterdam for his heretical views, Spinoza remained steadfast in his pursuit of truth. He lived a modest life as a lens grinder, declining offers of academic positions and financial support to maintain his intellectual freedom.

Spinoza’s legacy is profound. His work laid the groundwork for the Enlightenment and influenced later philosophers, including Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and Friedrich Nietzsche. His ideas on the nature of God, the human mind, and political freedom continue to resonate in contemporary philosophy and have inspired movements in liberalism, secularism, and rationalism.

Spinoza’s Impact on Modern Thought

Spinoza’s philosophy has had a lasting impact on various fields beyond philosophy. In psychology, his understanding of emotions as natural phenomena that can be understood and managed through reason has influenced modern approaches to emotional regulation and cognitive therapy. In political theory, his advocacy for freedom of expression and secular governance has informed modern democratic thought and the separation of church and state.

Moreover, Spinoza’s pantheism has found echoes in environmental ethics, where the interconnectedness of all things and the idea of nature as sacred are central themes. His vision of a universe governed by natural laws and his emphasis on understanding these laws through reason have made him a precursor to the scientific worldview.

Spinoza’s Philosophy and Religion: An In-Depth Exploration

Spinoza’s Philosophy: A Radical Departure from Tradition

Baruch Spinoza’s philosophy represents one of the most profound and original systems in Western thought. His ideas challenged the conventional metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical views of his time, ultimately leading to a radical rethinking of religion and its role in human life.

Substance Monism: God or Nature

At the core of Spinoza’s philosophy is the concept of substance monism, which he elaborates in his seminal work, Ethics. Spinoza begins by defining substance as “that which is in itself and is conceived through itself,” meaning that substance does not depend on anything else for its existence or understanding. From this definition, Spinoza concludes that there can only be one substance, which he identifies as God or Nature (Deus sive Natura).

This identification of God with Nature is a significant departure from the dualistic traditions of both Cartesian philosophy and classical theism, where God is often seen as a distinct, transcendent being who created the universe. For Spinoza, however, God is not a separate entity that exists outside the world; rather, God is the world. Everything that exists is a part of this singular substance, and all events in the universe are expressions of God’s infinite attributes.

The Rejection of Free Will

Spinoza’s conception of God as Nature leads to his deterministic view of the universe. In Ethics, Spinoza argues that everything that happens follows necessarily from the nature of God, which is expressed through the immutable laws of nature. Human beings, like everything else in the universe, are subject to these laws, and their actions are determined by the same causal chains that govern all natural events.

This determinism leads Spinoza to reject the traditional notion of free will. He contends that human beings are not free in the sense of being able to choose between genuinely open alternatives; rather, their choices are determined by prior causes, just like any other event in nature. However, Spinoza offers a different conception of freedom: true freedom, according to him, consists in understanding the necessity of natural laws and living in accordance with reason. By gaining knowledge of the causes that determine our actions, we can achieve a form of self-mastery and live in harmony with the natural order.

The Ethics of Rationality

Spinoza’s ethical philosophy is closely tied to his metaphysical views. He argues that human emotions are the result of inadequate ideas—confused and partial understandings of the world that lead to suffering and conflict. In contrast, emotions that arise from adequate ideas—clear and rational understandings of the world—are active emotions, which lead to empowerment and well-being.

Central to Spinoza’s ethics is the concept of the “intellectual love of God” (amor Dei intellectualis). This love is not an emotional attachment to a personal deity but rather the joy that comes from understanding the nature of reality and our place within it. For Spinoza, the highest form of happiness, or “blessedness,” is the knowledge of God (or Nature) that comes through the use of reason. This knowledge leads to a state of equanimity and peace, as we come to accept the necessity of all things and our connection to the infinite substance.

Spinoza and Religion: A Revolutionary Perspective

Spinoza’s philosophy has profound implications for traditional religious beliefs and practices. His ideas about God, scripture, and the nature of religious authority challenged the foundations of established religion and paved the way for a more secular, rational approach to spirituality.

Pantheism and the Rejection of Anthropomorphic Religion

One of the most controversial aspects of Spinoza’s thought is his pantheism—the view that God and Nature are identical. This stands in stark contrast to the anthropomorphic conception of God prevalent in many religious traditions, where God is viewed as a personal being with human-like qualities who intervenes in the world. Spinoza rejected this view, arguing that attributing human characteristics to God is a form of superstition and a product of ignorance.

For Spinoza, God does not have desires, intentions, or emotions, and does not engage in providential acts. The belief in a personal, interventionist God, according to Spinoza, leads to false religious practices based on fear and hope rather than on understanding. True piety, in Spinoza’s view, consists in understanding the natural order and living in accordance with reason.

Theological-Political Treatise: Religion, Freedom, and the State

In his Theological-Political Treatise (1670), Spinoza further developed his views on religion and its role in society. He argued that the Bible, while a valuable source of moral teachings, should not be seen as a source of scientific or philosophical truth. Spinoza advocated for a historical-critical approach to scripture, analyzing the Bible in the context of its historical and cultural background rather than interpreting it as the literal word of God.

Spinoza also addressed the relationship between religion and politics, advocating for the separation of church and state. He believed that religious authorities should not have power over civil matters and that individuals should have the freedom to interpret religious texts according to their own reason. Spinoza was a strong proponent of religious tolerance and freedom of thought, arguing that a state that respects individual freedom is more stable and prosperous.

The Excommunication: A Life of Intellectual Independence

Spinoza’s unorthodox views eventually led to his excommunication from the Jewish community in Amsterdam in 1656. The cherem (excommunication) declared against him was unusually harsh, reflecting the community’s fear of the radical implications of his ideas. However, Spinoza did not waver in his intellectual pursuits. He continued to develop his philosophy in relative isolation, maintaining a small circle of friends and correspondents who supported his work.

Despite his excommunication, Spinoza’s ideas had a lasting impact on religious thought. His emphasis on rationality, his critique of superstition, and his advocacy for religious tolerance influenced later Enlightenment thinkers and contributed to the development of modern secularism. Spinoza’s vision of a God who is identical with Nature and who is understood through reason rather than revelation remains one of the most original and provocative contributions to the philosophy of religion.

Spinoza’s Legacy in Philosophy and Religion

Baruch Spinoza’s work laid the groundwork for many of the intellectual movements that followed him, particularly the Enlightenment and modern secular philosophy. His ideas challenged the traditional views of God, religion, and ethics, offering instead a vision of the world as a unified, rational whole in which human beings find their place through the exercise of reason.

Spinoza’s philosophy has been interpreted in various ways over the centuries. Some have seen him as a heretic who undermined traditional religious beliefs, while others have viewed him as a pioneer of religious enlightenment who sought to free humanity from the shackles of superstition. In contemporary philosophy, Spinoza is often regarded as a precursor to modern ideas about determinism, ethics, and the nature of the self.

In religion, Spinoza’s pantheism has influenced various spiritual movements that emphasize the interconnectedness of all things and the divine presence in nature. His rejection of anthropomorphic conceptions of God and his advocacy for a rational, ethical life resonate with many who seek a spirituality based on reason and understanding rather than dogma and ritual.Baruch Spinoza was not only a great philosopher but also a revolutionary thinker in the realm of religion. His ideas about God, nature, and human freedom challenged the established religious and philosophical doctrines of his time, paving the way for a more rational and tolerant approach to spirituality. Spinoza’s legacy continues to inspire those who seek to understand the world through reason and to live in harmony with the truths they discover. His contributions to both philosophy and religion remain a testament to the power of intellectual courage and the enduring quest for truth.

Baruch Spinoza was a philosopher who lived ahead of his time. His commitment to rational inquiry, his courage to challenge established doctrines, and his profound contributions to metaphysics, ethics, and political philosophy make him one of the most important figures in Western thought. Spinoza’s life and work continue to inspire those who seek to understand the world through reason and to live in harmony with the truths they discover. His achievements in philosophy and his life as a model of intellectual integrity stand as a testament to the enduring power of ideas.

But was Spinoza right?

Albert Einstein explicitly stating, “I believe in the God of Spinoza.” This quote is often attributed to him but appears in letters and writings. Einstein’s views on God and religion were complex and nuanced, influenced by his admiration for Baruch Spinoza’s philosophy.

Einstein famously described his belief in a “cosmic religion” and expressed admiration for Spinoza’s idea of God, which is more aligned with a pantheistic view—seeing God as the natural laws of the universe rather than a personal deity. His views are primarily captured in his letters and interviews, notably in a 1929 interview with Rabbi Herbert Goldstein, where he said, “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings.”

Einstein’s letters and writings, such as the one to philosopher Eric Gutkind in 1954 (known as the “God Letter”), are sources for his thoughts on Spinoza’s concept of God.

For those of you who yearn to know more, I suggest exploring detailed resources or articles that dive into the topic you’re interested in. Whether you’re looking to deepen your understanding or explore related concepts, these sources can offer valuable insights.

Thomas Paine, A True Social Entrepreneur and Inventor

|

|

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again!” Thomas Paine

Unlike George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, or John Adams, who shaped the American experience with their democratic impulses and aspirations, Thomas Paine brought a unique perspective. He was a key figure in the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the struggles of British workers during the Industrial Revolution. Paine, one of the most remarkable political writers of the modern era, was the son of an English artisan who only became a revolutionary after arriving in America in late 1774 at the age of thirty-seven. He had never expected to take on such a role. However, inspired by the determination of the American people to resist British rule and captivated by America’s contradictions, possibilities, and energy, he committed himself to the American cause. Through his pamphlets Common Sense and The American Crisis, Paine encouraged Americans to transform their colonial rebellion into a revolutionary war, defining the new nation in a democratically expansive and progressive manner.

Paine was known for his inquisitive nature, sociability, compassion, and strong-willed, combative spirit. He was always ready to argue and fight for what he believed was right.

At the war’s end, Paine emerged as a popular hero, widely recognized as “Common Sense.” Joel Barlow, an American diplomat and poet who served as a chaplain in the Continental Army, famously remarked, “Without the pen of Paine, the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain.” Yet Paine’s work was far from over. He saw America’s political, economic, and cultural potential as extraordinary, but he did not view this potential as solely for Americans. Paine considered himself a “citizen of the world,” despite his English birth, American adoption, and French honors. Nonetheless, the United States always remained central in his thoughts and evident in his labors, and his later writings continued to influence the young nation’s events and developments.

However, Paine’s contributions were not always appreciated, and his affections were not always reciprocated. His democratic arguments, style, and appeal, along with his social background, confidence, and single-mindedness, antagonized many among the powerful, propertied, prestigious, and pious, creating enemies even within the ranks of his fellow patriots.

Founding fathers

On July 4, 1776, shortly after the Declaration of Independence was ratified, the Continental Congress tasked John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin with creating a seal to symbolize the new United States. They selected the image of Moses leading the Israelites to freedom. The Founding Fathers also inscribed a verse from Moses on the Liberty Bell: “Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.” (Leviticus 25:10)

When George Washington passed away in 1799, two-thirds of his eulogies referred to him as “America’s Moses.” One orator noted, “Washington has been the same to us as Moses was to the Children of Israel.”

In 1788, Benjamin Franklin observed the challenges that some newly independent American states faced in establishing a government. He suggested that, until a new code of laws could be agreed upon, they should be governed by “the laws of Moses” from the Old Testament. Franklin justified his proposal by noting the effectiveness of these laws in biblical times: “The Supreme Being… Having rescued them from bondage by many miracles performed by his servant Moses, he personally delivered to that chosen servant, in the presence of the whole nation, a constitution and code of laws for their observance.”

John Adams, America’s second president, explained his preference for the laws of Moses over Greek philosophy when establishing the Constitution: “As much as I love, esteem, and admire the Greeks, I believe the Hebrews have done more to enlighten and civilize the world. Moses did more than all their legislators and philosophers.” Swedish historian Hugo Valentin also credited Moses as the “first to proclaim the rights of man.”

Moses is prominently depicted in several U.S. government buildings due to his legacy as a lawgiver. In the Library of Congress, a large statue of Moses stands alongside a statue of the Apostle Paul. Moses is also one of the 23 lawgivers depicted in marble bas-reliefs in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol. The plaque’s overview states: “Moses (c. 1350–1250 B.C.), Hebrew prophet and lawgiver, transformed a wandering people into a nation and received the Ten Commandments.”

The other twenty-two figures have their profiles turned to Moses, which is the only forward-facing bas-relief.

Moses appears eight times in the carvings that adorn the ceiling of the Supreme Court’s Great Hall. His face is featured alongside other ancient figures such as Solomon, the Greek god Zeus, and the Roman goddess of wisdom, Minerva. The east pediment of the Supreme Court building depicts Moses holding two tablets. Representations of the Ten Commandments are also found carved into the oak courtroom doors, the support frame of the courtroom’s bronze gates, and in the library woodwork. A particularly controversial image is situated directly above the chief justice’s head. At the center of a 40-foot-long Spanish marble carving is a tablet displaying Roman numerals I through X, with some numbers partially hidden.

In the Christian tradition, “Moses” is often metaphorically referred to as a leader who delivers people from dire circumstances. Several U.S. presidents have invoked the symbolism of Moses, including Harry S. Truman, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama, who called his supporters “the Moses generation.”

Winston Churchill, in his 1931 essay “Moses—the Leader of a People,” used the story of Moses to advocate for strong leadership in Britain, asserting that “human success depends on the favor of God.” He rejected the notion that Moses was merely a legendary figure, instead describing him as “the supreme law-giver, who received from God that remarkable code upon which the religious, moral, and social life of the nation was so securely founded… [and] one of the greatest human beings with the most decisive leap forward ever discernible in the human story.” Churchill emphasized the contemporary relevance of Moses, suggesting that “we may believe that they happened to a people not so very different from ourselves.”

Churchill implied that the Ten Commandments were a foundational set of laws: “Here [on Mount Sinai], Moses received from God the tables of those fundamental laws, which were henceforth to be followed, with occasional lapses, by the highest forms of human society.”

In later years, theologians linked the Ten Commandments to the development of early democracy. Scottish theologian William Barclay described them as “the universal foundation of all things… the law without which nationhood is impossible. Our society is founded on it.” Pope Francis, addressing the U.S. Congress in 2015, emphasized the importance of just legislation to maintain unity, stating, “the figure of Moses leads us directly to God and thus to the transcendent dignity of the human being.”

Abraham-Louis Breguet

Every great watch house has a remarkable origin story, and for Breguet, it begins with its founder, Abraham-Louis Breguet. Born on January 10, 1747, in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, Breguet faced early adversity when his father passed away when he was just 11 years old. His mother remarried her late husband’s cousin, Joseph Tattet, who was part of a family already established in the watchmaking business with a sales office in Paris. In 1762, Tattet took young Breguet to Paris, where he became an apprentice to a master watchmaker at Versailles, though the identity of this mentor remains unknown.

After completing his apprenticeship, Breguet is speculated to have worked with renowned horologists such as Ferdinand Berthoud or Jean-Antoine Lepine. He certainly furthered his education in mathematics at the Collège Mazarin, under the guidance of Abbé Marie. Marie, who also tutored the children of the Comte d’Artois, introduced Breguet to the aristocratic families who would later become his prestigious clientele.

While many know Breguet for his invention of the tourbillon, pioneering the guilloché technique on watch dials, and his reputation as the finest watchmaker of his era, there are intriguing facets of his legacy that are less well-known. For instance, Napoleon Bonaparte was a client before he ascended to the role of emperor. Breguet also crafted the most complicated pocket watch ever made for Marie Antoinette, although it was completed only after her execution. Additionally, the Breguet family expanded their legacy beyond horology, venturing into aviation and introducing the telephone to France.

Join us on a journey through time as we explore some of Breguet’s most significant historical achievements in Paris and beyond.

1783–1827: Breguet Creates the most complicated pocket watch ever created for Marie Antoinette.

Marie Antoinette’s pocket watch, fittingly for one of history’s most infamous royals, remains one of the most extraordinary and complex timekeeping inventions ever created. Symbolic of her tumultuous and brief life, the queen commissioned the watch in 1783, requesting every possible complication and refinement of the time, with no expense spared. Gold was to be used wherever possible, and the watchmaker was given unlimited time to complete it.

The self-winding masterpiece features a minute repeater, a full perpetual calendar, the equation of time, a power reserve indicator, a metallic thermometer, an on-command independent seconds hand, a small sweep seconds hand, a lever escapement, a gold Breguet overcoil, and shockproofing. This intricate creation has been compared to shrinking a cathedral clock into a pocket watch. Unfortunately, it took 44 years to complete and was finished by Abraham-Louis Breguet’s son long after Marie Antoinette’s execution during the French Revolution on October 16, 1793. The pocket watch now resides in the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem.

Breguet also made significant innovations by producing the first automatic wristwatches in the world, delivered to the Queen of Naples, a relative of Napoleon. The meticulous Breguet archives in Paris detail the brand’s illustrious clientele since the 18th century, including kings and emperors of France. These records also note transactions with modern figures like Winston Churchill and the romanticized Marie Antoinette, who purchased her final Breguet pocket watch while imprisoned and awaiting the guillotine during the French Revolution. Each of these stories about Breguet products and their famed owners could stand alone as independent discussions.

The Invention of the Perpetual Watch

The origin of the self-winding watch, initially called the “perpetual watch,” remains uncertain. While Louis Perrelet is credited with the principle of the rotor, Breguet used a different kind of moving weight known as the “masse à secousses.” This innovation powered two barrels that provided a “power reserve”—a term coined by Breguet—of 60 hours. Breguet’s experimentation with multiple barrels continued throughout his career, culminating in the use of four barrels.

Although the concept of the oscillating weight eventually prevailed, Breguet’s contributions included several other innovations. For his repeating watches, a particular specialty, he replaced the traditional straight gong across the rear plate with curved gongs wound around the movement, a design still in use today.

The History of Breguet

The history of the Breguet brand spans four centuries, rich with inventions and innovations that have profoundly shaped the entire history of watchmaking. Given the numerous significant events in Breguet’s past, we will chart the path from its origins to the present in two articles.

The brand takes its name from its founder, Abraham-Louis Breguet, who was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, on January 10, 1747. His ancestors were French Protestants who fled to Switzerland in 1685 to escape the intense persecution that followed the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which had previously ended the religious wars in France. Despite the prohibition against leaving the country, around 400,000 Protestants, including the Breguet family, risked their lives to escape France.

Abraham-Louis faced early adversity when his father, Jonas-Louis, died when he was just eleven years old. Soon after, his mother, Suzanne-Marguerite Bollein, remarried her late husband’s cousin, Joseph Tattet, a member of a family of watchmakers. In 1762, Tattet took young Breguet to Paris, where he was apprenticed to a master watchmaker in Versailles, though this mentor’s name remains unknown.

Upon completing his apprenticeship, Breguet worked for two of the most esteemed watchmakers of the era, Ferdinand Berthoud (1727–1807) and Jean-Antoine Lépine (1720–1814). Recognizing the importance of mathematics for his craft, Breguet continued his education with evening classes at the Collège Mazarin under Abbé Marie. Impressed by Breguet’s talent and intelligence, Marie played a crucial role in introducing him to the French Court and the aristocracy, who would later become his clientele.

Despite the loss of his mother, his stepfather, and his mentor Marie in quick succession, Breguet managed to care for his younger sister and, in 1775, at the age of 28, established his own business at No. 39, Quai de l’Horloge, on the Ile de la Cité by the River Seine near Notre Dame. That same year, he married Cécile Marie-Louise L’Huillier, the daughter of an established Parisian bourgeois family, likely using part of her dowry to fund his new enterprise.

Innovations and Legacy

Breguet is known for numerous groundbreaking innovations, including the invention of the tourbillon and pioneering the use of the guilloché technique on watch dials. His client list read like a who’s who of the elite, including royalty and influential figures. Among his notable commissions was the creation of the most complicated pocket watch for Marie Antoinette, although it was completed long after her execution.

Breguet’s influence extended beyond watchmaking into fields like aviation and telecommunications. His legacy is preserved in meticulous records housed in the Breguet archives in Paris, documenting interactions with clients such as Napoleon Bonaparte, Winston Churchill, and many others.

The Perpetual Watch and Other Innovations

The origin of the self-winding watch, known as the “perpetual watch,” is debated, with Louis Perrelet often credited for the rotor principle. However, Breguet introduced a different mechanism, the “masse à secousses,” which powered two barrels and provided a power reserve—a term Breguet coined—of 60 hours. Throughout his career, Breguet experimented with multiple barrels, even using four towards the end.

Breguet also revolutionized repeating watches by replacing the traditional gong with curved gongs wound around the movement, a design still utilized today. These innovations and more highlight Breguet’s lasting impact on horology, cementing his status as a pioneer and visionary in the watchmaking world.

Thanks to Abbé Marie’s introductions, Abraham-Louis Breguet quickly began receiving orders from the aristocracy. Among his first commissions were a self-winding watch for the Duc d’Orleans in 1780 and another for Marie Antoinette in 1782. These self-winding, or “perpétuelle,” watches brought him considerable fame both at the court of Versailles and throughout Europe. While he wasn’t the first to create a self-winding watch, Breguet is widely credited with producing the first truly reliable and effective one.

From 1787 to 1823, records show that Breguet sold sixty “perpétuelles.” Though there are no records from 1780 to 1787, it is estimated that another twenty to thirty pieces were produced during that period.

The French Revolution posed significant dangers for Breguet due to his close ties to the aristocracy and the royal court. Fortunately, he had become friends with revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat, whose sister Albertine made watch hands for him. Tradition holds that Breguet saved Marat from an angry mob by disguising him as an old woman, allowing them to escape safely.