Why Do Child-like Observations or Child-like Listening Work?

“Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.” —Pablo Picasso “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.” —Pablo Picasso

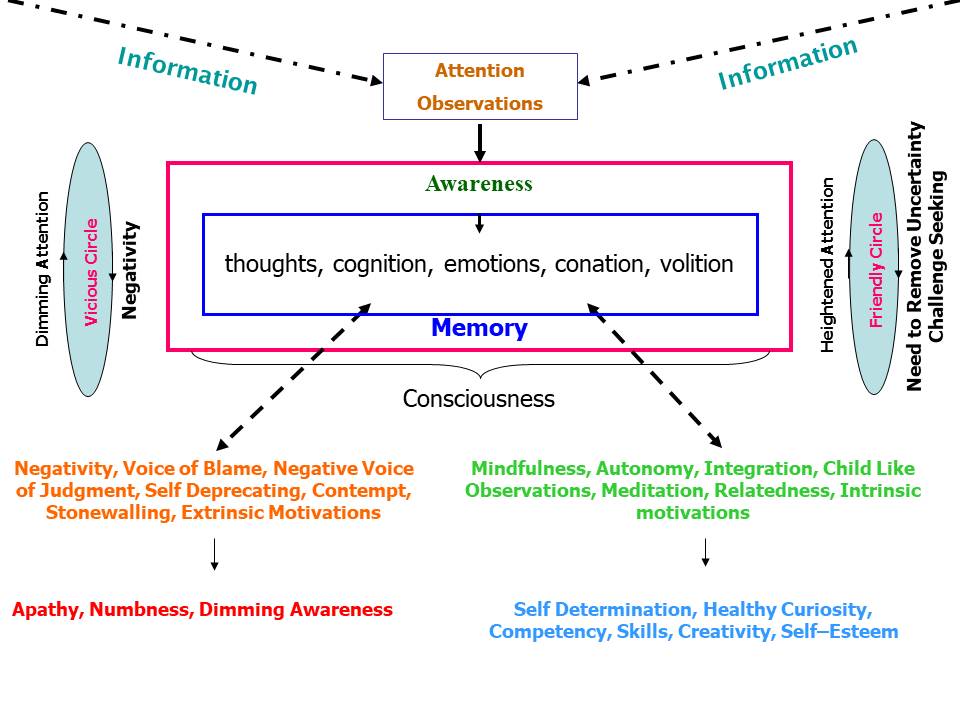

Childlike observations and listening work because they are the quickest route to noblification and finding virtue. Children purify easily. There are no hang-ups. The mind cannot be purified without seeing things as they really are (insights). Children see things as they really are. Adults don’t. Our past programming skews these observations. Adults refuse to see everything there is to see, to draw novel distinctions, or worse, they sometimes have no interest and see with greed, selfishness, hatred, delusions, and ignorance.

Children also see aesthetically. They see the beauty in everything they do. If children could explain it in adult language, they would tell you that all their experiences, from drawing to playing in a sandbox, are aesthetic experiences. Just as music facilitates attention, aesthetically pleasing objects help with strong focusing of vision and observation. The Buddhist tradition speaks directly about the hindrances encountered in the spiritual journey.

There is a story about Mother Teresa of Calcutta. After praising her extraordinary work, an interviewer for the BBC remarked that, in some ways, service might be easier for Mother Teresa than for us ordinary householders. After all, she has no possessions, no car, no insurance, and no husband. “This is not true,” she replied at once. “I am married too.” She held up the ring that nuns in her order wear to symbolize their wedding to Christ. Then she added, “And he can be very difficult sometimes!” The hindrances and difficulties of spiritual practice are universal.

|

|---|

There is a traditional analogy comparing our nature to a pond, where the goal of practice is to see the pond’s depths clearly. Desire acts like beautifully colored dyes that obscure our vision. Anger turns the pond into a boiling-hot spring, preventing us from seeing far. Sloth and torpor form a thick layer of algae on the surface. Restlessness is like a strong wind creating waves. Doubt stirs up mud from the bottom, clouding the water.

How do we dismantle these hindrances? Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield, in their book Seeking the Heart of Wisdom, explain it best:

Certainly not by suppression. Suppression doesn’t work because it is a form of aversion. The most direct way is to be mindful of these hindrances and transform them into the object of meditation. Through the power of mindfulness, we can use awareness of them to bring the mind to greater freedom.

There is a second way of working with hindrances, recommended when they are particularly strong. By cultivating their opposite states as a balance or remedy, we can weaken the hindrances and free ourselves from strong entanglement with them.

When concentration becomes strong and mindfulness is well developed, it is possible to simply let go of these states as soon as they arise. This letting go involves no aversion; it is a directed choice to abandon one mind state and redirect concentration to a more skillful object such as the breath or a state of mental calm.

How do we apply these methods in practice? For example, if sense desire arises, what do we do? We look directly at this mental state and include it in our field of awareness. First, make a soft mental note of it: “desire, desire.” We can observe sense desire just as we observe the breath or sensations in the body. When a strong desire arises, turn all your attention to it and see it clearly. What is this desire? How does it feel in the body? What parts of the body are affected—the gut, the breath, the eyes? What does it feel like in the heart and mind? When it is present, are we happy or agitated, open or closed? Note “desire, desire” and see what happens to it. Pay meticulous attention.