That so few now dare to be eccentric, marks the chief danger of our time.

—John Stuart Mill, On Liberty

IT IS USUALLY ASSUMED, ERRONEOUSLY, THAT THE UNITED STATES HAS NEVER BEEN A MONARCHY!.

From 1859 to 1880, Joshua Abraham Norton was the emperor of the United States. His accession to the American throne was proclaimed by an edict published in the San Francisco Bulletin on September 17, 1859:

At the peremptory request and desire of a large majority of the citizens of the United States, I, Joshua A. Norton, declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these United States, and in virtue of the authority thereby vested in me, do hereby order and direct the representatives of the different states of the Union to assemble in Musical Hall, of this city, on the first day of February next, then and there to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring and thereby cause confidence to exist, both at home and abroad, both in our stability and in our integrity.

[Signed]

Norton I, Emperor of the United States, and protector of Mexico.

Born in London in 1815 and raised in South Africa, Norton made a small fortune during the California Gold Rush by speculating in property. In 1853, he gambled a quarter of a million dollars on an effort to corner the rice market in San Francisco, buying and stockpiling all the available supply and thereby artificially inflating the price. However, just as he was about to cash in, several ships laden with rice sailed into the bay, glutting the market. Prices plummeted, and Norton went bust. He was soon reduced to working in a sweatshop and living in a seedy rooming house.

Most people would have been daunted by such a reversal of fortune, but not the doughty Norton. He discovered his true vocation: ruling an empire. He began confiding in his friends that he was really Norton I, emperor of California. In 1856, the same year he filed for bankruptcy, he also issued his first imperial edict, imposing a monthly tax of fifty cents on sympathetic merchants in San Francisco to bankroll the fledgling empire. By 1859, he had decided that California was not big enough for him, and he annexed the whole United States.

He became instantly famous. He suspended the Constitution and dissolved both the Republican and Democratic political parties on the grounds that “their existence engendered dissensions.” He printed his own money in twenty-five- and fifty-cent denominations, which were accepted freely in most shops and restaurants in San Francisco. Yet as emperor, he felt that he was entitled to more, and he tried to negotiate loans of several million dollars from the banks, which found tactful ways of evading the imperial demands.

Norton took his responsibilities seriously. For more than twenty years, he patrolled the streets, seeing to it that the sidewalks were unobstructed and the streetcars ran on time. He never missed a session of the state Senate, where a chair was reserved for him, and he attended a different church every week so as to avoid sectarian strife in the empire. The emperor was a benevolent despot for the most part, but when his authority was challenged, he responded with an iron fist. When Maximilian assumed the throne of Mexico, which was an imperial protectorate, Norton sentenced him to death as a usurper.

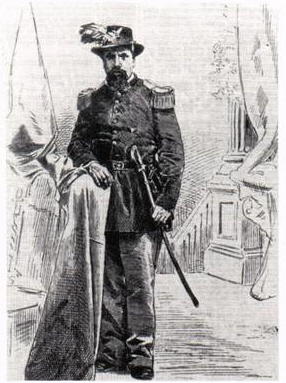

The emperor always wore a blue military uniform with golden epaulettes, which had been given to him by army officers, with a tall, plumed beaver hat, a sword, and a rosette. In 1869, when his uniform became shabby, he issued another edict:

Know ye to whom it may concern that We, Norton I, Emperor Deigratia of the United States and Protector of Mexico, have heard serious complaints from our adherents and all that our imperial wardrobe is a national disgrace, and even His Majesty the King of Pain has had his sympathy excited so far as to offer us a suit of clothing, which we have a delicacy in accepting. Therefore, we warn those whose duty it is to attend to these affairs that their scalps are in danger if our said need is unheeded.

The city’s Board of Supervisors, mindful of its scalps, appropriated the money to buy him a new uniform. The emperor, touched by this gesture, knighted the whole board.

The King of Pain referred to in the emperor’s edict was a fellow street royal, a patent-medicine salesman who wore scarlet underwear, a heavy velour robe, and a stovepipe hat decorated with ostrich feathers. The king rode a black coach drawn by six white horses—considerably more horsepower than the crowded city streets required.

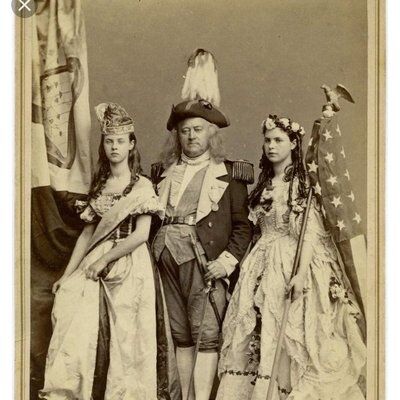

J.J. McBride a.k.a. The King of Pain

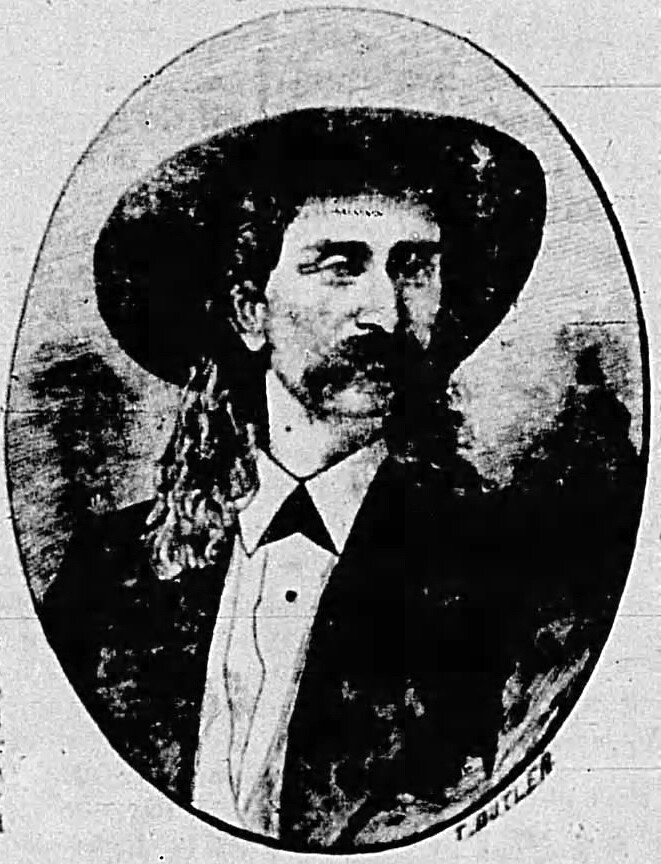

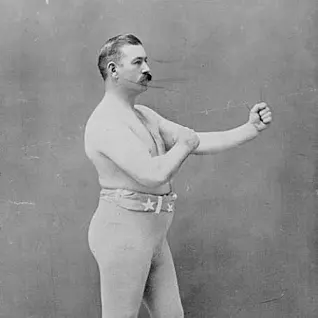

San Francisco, always renowned as the capital of the freakish and fantastical, had its golden age of weirdness in those post-Gold Rush years. Another of Emperor Norton’s subjects was Oofty Goofty, the Wild Man of Borneo, who walked about swathed in fur, making strange animal cries. He supported himself by allowing passersby to kick him for ten cents, cane him for twenty-five cents, and hit him with a baseball bat for fifty cents. The boxing champion John L. Sullivan, getting his half-dollar’s worth, sent Oofty Goofty to the hospital with a fractured spine.

Oofty Goofty

There was also a phrenologist named Uncle Freddie Coombs, who bore a striking resemblance to George Washington. He took to wearing knee breeches, a powdered wig, and a tricorn hat, and went about the city with a banner proclaiming himself to be “Washington the Second.”

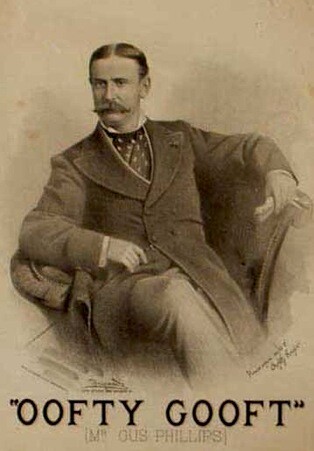

Montgomery Street was the beat of the Great Unknown, an impeccably attired, vaguely theatrical gentleman with a gold-headed cane who took a stroll every afternoon, mysteriously averting his gaze and speaking to no one. After many years of this enigma, there was a public reception in Pacific Hall, where it was revealed to everyone who was interested enough to pay twenty-five cents that the Great Unknown was a retired German tailor named William Frohm.

Great Unknown.

In their lifetimes, Emperor Norton, the King of Pain, Oofty Goofty, Uncle Freddie Coombs, and the Great Unknown were regarded as harmless eccentrics, a source of delight, and even a sort of strange asset to the community. Today they would be declared to be suffering from any number of well-defined mental illnesses, vigorously battered with tests and physical treatments, diagnosed, tranquilized, stabilized, and forced to be “normal,” whether they wanted it or not. Yet there is no evidence that these men were unhappy or that their lives would have been improved in any way by being compelled to surrender their eccentricities and conform. If Emperor Norton had been “cured,” he might have had a normal, conventional, dull career as a clerk or salesman—a miserable comedown for a man who had wielded the scepter. His life would have been impoverished, and so would that of the society he lived in. When Norton died in 1880, the San Francisco Chronicle ran the headline “Le Roi Est Mort.” The police were summoned to ensure order among the huge crowds of people who came to the funeral parlor to pay their last respects to their beloved monarch. All flags in the city were flown at half-mast. Thirty thousand mourners attended the lavish graveside service, and many more than that turned out to see the funeral procession pass through the streets of San Francisco to the Masonic Cemetery.

Emperor Norton and his court pose a challenge to the assumption that underlies all modern psychology: that we know more than we used to about the mind and therefore are doing things better now. In fact, a strong case could be made that even though nineteenth-century Californians knew nothing about brain-cell synapses or neurotransmitters, delusional grandiose mania, or borderline syndromes, in humanitarian terms they got it much better than we do now.

Why is that? Precisely what does it mean, in the first place, to say that Emperor Norton and the others were eccentric?

The dictionary tells us that an eccentric is someone who deviates from the conventional or established norm and is different from the rest of us—hardly a definition that is likely to satisfy a trained psychologist. That description applies just as well to a criminal or a person with a birth defect.

What does science have to say on the subject? Ten years ago, when I first began asking these questions, I undertook a thorough search for some answers through the vast, forbidding tundra known as the scientific literature. One would expect that abnormal or clinical psychology, which has produced definitive treatises on every conceivable deviation from normal behavior, must surely have established a sound, widely tested profile of the eccentric, one that carefully distinguishes the syndrome from other, harmful forms of mental aberration. Yet, in fact, there is next to nothing to be found on the subject of eccentricity in modern scholarly literature. Because eccentrics tend to be healthier than most people, they rarely seek the services of the medical profession, and the medical profession, as a rule, is not very interested in those who do not seek it out.

In the field of experimental psychology, it is an open secret that we have learned a great deal about how penniless undergraduates perform in narrow and sometimes deliberately deceptive experiments, while psychiatrists, on the other hand, know about every possible variation in the behavior of people who have had mental breakdowns. The rub, from a scientific point of view, is that those two groups rarely overlap, so most of the theoretical knowledge obtained by the experimental psychologists is useless to the psychiatrists who are dealing with patients. Meanwhile, almost nobody is studying adult nonpatients, the vast bulk of humanity.

Of the four best-known textbooks on psychiatry, three make no mention of eccentricity. The fourth describes it, cryptically, as a form of “predominantly inadequate or passive psychopathy,” adding that it is “usually difficult to distinguish the symptoms of eccentricity from schizophrenic manifestations.” These summary statements are tossed off with nonchalance, and there is no mention of the fact that they are based upon a database of zero patients and research subjects and upon clinical observations that are at best haphazard.

Thus, it appeared to me that actual scientific knowledge about eccentrics was virtually nonexistent. Nature abhors a vacuum, and so does a scientist. Since no study of eccentricity existed, I decided to begin my own. It occurred to me that it would be a great advantage to psychology to have a basic understanding of the thought processes of people who come to regard themselves and who are regarded by others as eccentric, if only to help distinguish their behavior from certain forms of mental illness. Such a study would also be an ideal way to learn about illogical thought processes, and it might help us to understand more about the deep human mystery of schizophrenia. Furthermore, given the frequent association of eccentricity with genius and the ability to conceive startlingly original artistic and scientific breakthroughs, it seemed to be an obviously worthwhile subject for psychological research. The annals of eccentricity include, in addition to Emperor Norton and Oofty Goofty, such names as William Blake, Alexander Graham Bell, Emily Dickinson, Charlie Chaplin, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, not to mention Albert Einstein and Howard Hughes. If we could gain even the barest glimpse into how all those people came to be the way they were, it might just help the rest of us to be more creative, more original, and better at being ourselves.

The poem below is from the hymn “The Spacious Firmament on High,” written by Joseph Addison. It was first published in The Spectator, a daily publication founded by Addison and Richard Steele, in an issue dated August 23, 1712. The hymn is a paraphrase of Psalm 19 from the Bible and celebrates the beauty of the heavens as a testament to God’s creation.

The spacious fermament on high,

With all the blue etherial sky,

And spangled heavens, a shining frame,

Their great original proclaim.

The unwearied sun, from day to day,

Does his Creator’s power display,

And publishes to every land,

The work of Almighty hand.

Soon as the evening shades prevail,

The moon takes up the wond’erous tale,

And nightly to the list’ning earth

Repeats the story of her birth.

Whilst all the stars that round her burn,

And all the planets in their turn,

Confirm the tidings as they roll,

And spread the truth from the pole to pole.

What tho’ in solemn silence, all

Move round this dark terrestrial ball,

What tho’ no real voice, nor sound,

Amidst their radiant orbs be found,

In reason’s ear they all rejoice,

And utter forth a glorious voice;

For ever singing as they shine,

THE HAND THAT MADE US IS DEVINE

Read the Fable Below

There were only three monks in the world a very long time ago, and only three. They were deeply worried that their decisions would have an impact on the monastery’s destiny. Their goal was to inquire of any intelligent man how to preserve the future. Nobody could provide the answer.

To discover the solution, they embarked on a global journey. One man said, “The wise rabbi far away on the other side of the world might have the answer,” halfway around the globe. To find the knowledgeable rabbi, they packed.

They eventually located him. The Rabbi gave them advice on how to treat all of their ailments and other issues, but he was completely clueless on how to keep the monastery afloat. The monks were so let down that they packed up and set on departure. Rabbi called them back as soon as they opened the door, telling them that he was now positive that one of them was closely connected to God and might even be profit such as Abraham. The Rabbi further explained to them that this is merely a test from God.

The monks believed that because Rabbi was too elderly, he had either lost his wits or gone insane. After thanking him, they departed mocking the old rabbi.

Upon returning to the monastery, every monk considered the sage’s parting remarks and concluded, “It is not possible that I am related to God, or I might be a profit.” Every monk therefore concluded that if the Rabbi is right and I am unrelated to God, then at least one of the other two must be.

Thus, each monk started to regard the other two with the utmost reverence, thinking that they might be related to God.

After few months, each monks thought I must be related to God after realizing how much respect each was getting from the other two.

The monks also came to the conclusion that I should wear nicer clothes if I am related to God. Each dressed more elegantly as a result. “If I am related to God, I should have better housing,” they embarked on adding trees and flowers. Hence, they created the tastiest meals, painted the monastery, sang, drew, created artwork, made sculptures, and more. CREATIVITY MOTIVATION!!!

Globally, people wrote and sung about the just constructed, breathtaking monastery. Many traveled from all over the world to view and savor the delectable food, plants, and flowers; some even made the decision to remain. And those who stayed preserved the monastery’s future. The fable’s lesson is that God is a part of all of us.

The best gift a person can offer themselves is respect for themselves.